Is inflation back, and in which form?

By Federico Sturzenegger

Universidad de San Andres, Harvard Kennedy School and HEC

I want to start thanking Cedric Tille and the Geneva Graduate Institute for the invitation to address all of you this night in lovely Geneve. The title is clear: inflation is back. Yes, it is back. No doubt about that. No question about that. The question is in which form. Is it permanent, is it transitory? Is it the same old inflation that we read about and studied in the 70s?

Well if you need to discuss inflation, it is clear that you have only one thing to do. What is that? You call an Argentinean! You sure don’t think they know how to solve inflation, but you are sure they know something about inflation. So here I am!

To start with let me start with what I call the Argentina’s inflation theorem. The Argentina’s inflation theorem says that “the number of explanations for inflation is proportional to the level of inflation”. And this is the first thing you should know. When inflation goes up, people start with all kind of (mostly crazy) explanations for inflation: “It’s the beef producers! It’s greed inflation! It’s the US Dollar! It’s Putin! It’s monetary policy, it’s fiscal policy!” You’re going to get thousands of stories. So, this becomes very confusing for those that have to come up with an expectation of inflation in their daily lives.

I would say that inflation is always the same, has the same causes, and should be interpreted in the same way. But it is true that inflation this time comes after 40 years of successful disinflation. And this is a big difference with the 1970s because inflation has caught everybody off guard. So inflation has come the same way but its implications will not be exactly the same.

Let’s start our discussion revisiting any standard intermediate macro textbooks to discuss what we know about doing monetary policy with inflation targeting using the interest rate as a policy tool. If you go there look for the section on a new-keynesian model with a fixed interest rate. The textbook will tell you that that’s a system which is totally un-anchored. If you don’t remember this, I recommend you go to the textbook. Fast. Why is this the case? To understand this result imagine you have a fixed interest rate and people increase prices, for whatever reason, it really doesn´t matter why for the argument. But if they increase prices, they put pressure on money demand that increases the interest rate. But remember that the central bank wants to keep the interest rate fixed, so the pressure upwards in the interest rate pushes the central bank to print money to lower the interest rate to its policy target. In doing so, the central bank ends convalidating the price dynamics. And that’s why with a fixed interest rate, the system become un-anchored. And this is in the textbook.

How do you anchor the system and inflation expectations in such a framework? You anchor it by having the interest rate react strongly when inflation increases something that we call the Taylor principle. This means that, whenever inflation increases, you must increase the interest rate more than what inflation increased. Why does this anchor the system? Because in this way you build credibility. It’s true that our models don’t really explain credibility. We know little about credibility, where it comes from, how it’s built, how it’s lost or earned. So that’s a little bit obscure there. Mathematically the system becomes pinned down because once you add that reaction by the central bank the system from a mathematical point of view becomes totally unstable, and when the system is totally unstable there’s only one equilibrium because if you don´t go straight to the equilibrium the whole thing blows apart. Yes, a bit weird. As an economist I am very comfortable with that because it is a typical way to find an equilibrium in macro models. In the real world however, people may go in a deviant path for a while until they realize that some transversality condition is not satisfied. What I’m trying to say is that you have a system that requires very strong assumptions of rationality for it to be anchored. And this begs the question of whether once it is de-anchored, how easy it is to bring it back to the equilibrium. The truth is that we really don´t know.

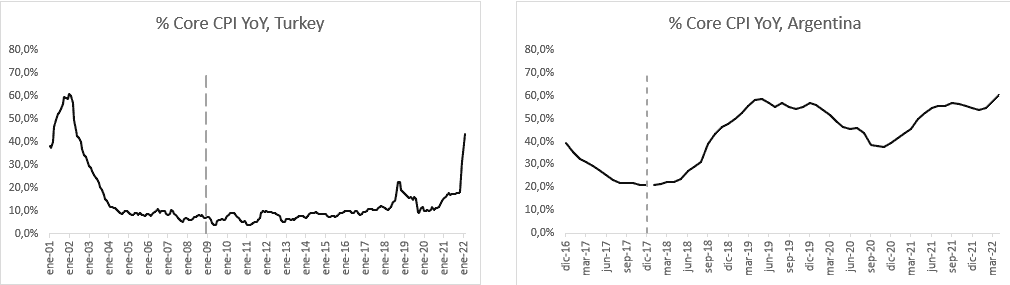

On this let me share with you two stories. These are the stories of two inflation targeting regimes that had a credibility loss, which was then impossible to recover. One of these cases, on the right side of my first figure I had to live through because it is Argentina. The graph for Argentina starts when I launched the inflation targeting regime in early 2016. In the initial two years we managed to bring down inflation from 40% to about 17%. The economy was growing, and we won the elections at the end of 2017. But when we won the elections, the government decided it was time to push for more expansionary fiscal and monetary policy. The executive changed the inflation target at the end of the year and that undermined credibility. The change in the targets is identified by the vertical dashed line in the graph. It is evident what happened afterwards. I left a few months later around June, but you see that after I left things really didn’t improve. The Government tried everything to restore credibility: an IMF program to solve the financing problem, they implemented a Volcker style zero monetary base growth program. Nothing worked, and two years later the inflation rate was 50%. This was an example in which credibility was compromised and then impossible to rebuild.

The other example is Turkey. Turkey had a very successful disinflation program at the beginning of the 2000s bringing inflation down from 70% to about 10% in a few years. By 2009, their inflation target was 4.5%. And even though they were close, they were not reaching it, so they decided to change the target to bring it up to where inflation was. But after they did that, they never again managed to get inflation down below 10%. And it’s really been uphill from there for them.

I think we don’t know for sure how we recover credibility. Is it enough to tighten interest rates to restore normalcy, or will something more dramatic be necessary? We simply don’t know.

Now let me move to the reasons why inflation is back. The reason that everybody talks about is shocks with a particular emphasis placed on the energy shocks, particularly after Russia´s invasion of Ukraine.

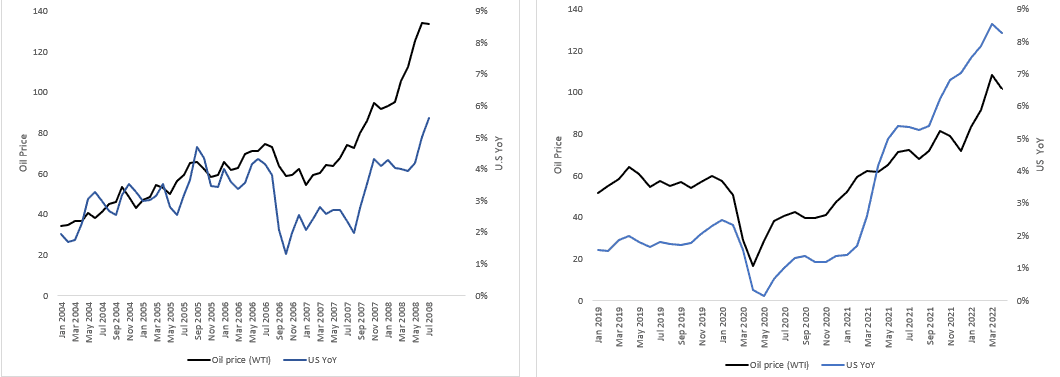

To discuss this issue let´s look at my second figure. I want you to look at this graph for a minute and think through it with me. Here on the right-hand side, I have the recent evolution of the price of oil and of US inflation. You see that the price of oil went from around 60 to 120. This is WTI. As the price of oil doubles inflation goes from around two to eight. And everybody says, “well, there are supply shocks. There’s Ukraine. The price of oil went up, and this is the reason inflation goes up”. But now look to the graph to the left. The graph on the left covers the period from 2004-2008. During this period the price of oil went from 40 to 140. So, oil multiplied by three and a half a much larger movement than that of 2021-2022. However, inflation barely moved.

Well, that’s kind of interesting. And when I find something interesting like that I say, how do I think about this? And to do that I always like to start with the most canonical simplest model I can imagine. So let me think of a model where money is exogenous, and prices are totally flexible. You may think about the quantitative theory of money if that helps. Imagine M, the quantity of money, is fixed, and a price in the economy changes (for example gas prices). But if people spend more in the good whose price has increased, that means they have less to spend on other goods (remember M is fixed). So, the other prices are going to fall. The price levels are determined by M not by a relative price. In fact, we don’t have many models where we explain inflation as a function of relative prices. I think we don´t have any model where inflation depends on relative prices. So, there is a huge disconnect here between the theory and policy.

Now, in the new Keynesian framework, monetary policy, we said, is endogenous! So, when you face a supply shock it is quite common that the central bank operates in a way that accommodates the shocks, particularly to avoid forcing deflation on the other goods. So, in the end you do have inflation. In practice you’re going to see a correlation between supply shocks and inflation. But the correlation is because monetary policy generates the correlation. In other words, when you see the correlation between the supply shocks and inflation that we’re seeing now, I think it speaks more about monetary policy than about the shocks themselves. We’ve had this discussion in Latin American countries for ages, in particularly regarding something we call the pass-through of exchange rates to inflation. And I tell my students that the pass-through is not a God-given god-forsaken number. The pass-through is going to be different if Guillermo Ortiz or Agustin Carstens are president of the Central Bank of Mexico than if other people are president of that central bank. It depends on the credibility and the stance of monetary policy. So, I think the shocks do not generate inflation per se. If the shock comes with inflation, it is because monetary policy is increasing inflation in the face of the shock.

Another common theme is that of salient prices: the idea that if one very visible price goes up all prices go up. On this issue I’ve studied pricing behavior in Argentina to test this idea. To do so I looked at pricing behavior at the weekly frequency to see how it related to salient prices changes vis a vis general expectation of inflation. And what I find in those analyses is that these salient prices play no role in the pricing behavior. So here again we are not going to find anything special.

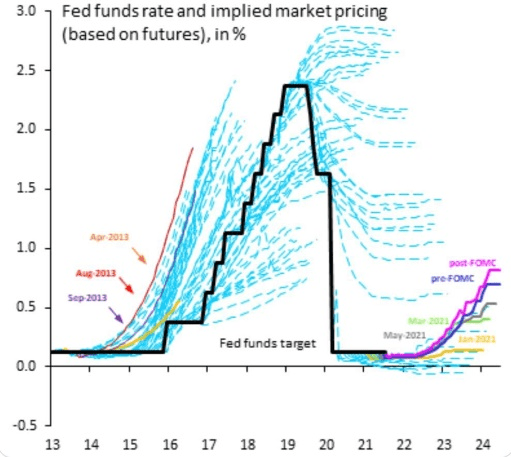

So, if salient prices do not explain expectations, what does? A clue may be given in my third figure, which shows the FED funds rate and the median market projections for the rate going forward. Before this upsurge in inflation the Fed had sustained rates which were lower than expected for many many years. I don’t have econometrics, I don’t have good theoretical model for this, but if I think that if a central bank for 10 years implements a monetary policy that is more expansionary than what the market thinks it should be doing, sooner or later that has to build into expectations. I don’t know how fast or how slow, but when I think about expectations, I would check how monetary policy performed relative to expectations, and in the case of the US this metric suggests that the Fed was overly expansionary for many years.

Now, if on top of this monetary authorities say that inflation is because of the war Ukraine, that it’s a supply shock, that it’s transitory, what are you really saying? You say you’re not moving the interest rate. And if you say, you’re not moving the interest rate, you’re violating the Taylor principle, right on. You’re telling people that your monetary policy is totally passive to the shocks that are happening in the economy. And I think that really puts you in a very bad spot.

So I would say that everything we’ve discussed means that inflation has come in the same old way. In its old and unique self. Inflation is, one more time, the result of easy monetary policy. The rest of the stories are necessary noise already predicted by the Argentina theorem of inflation. This latitude has been compounded by the fictitious idea that inflation was this time somewhat different. That inflation had died. Unfortunately, all that turned out to be nonsense.

Now that we’ve settled that issue, let’s look into a way way in which inflation is, this time, somewhat different. And this occurs because inflation comes after 40 years of successful central banking. Very persistent low inflation led to the belief that inflation would continue to be low in the future. That central banks would do the right thing to keep it in check. And this view led to the expansion of fixed rate dollar denominated liabilities all around the world.

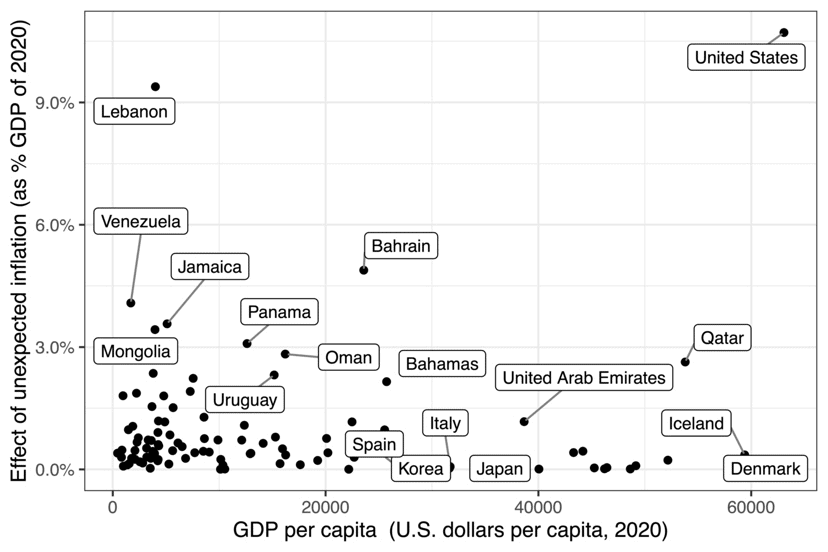

With my colleague from Harvard, Nair Gautam, we’ve looked at how the return of inflation has affected income across countries. Of course, there are many effects because liabilities in dollars are issued by different players. So, we focus on sovereigns. The question we try to answer is which sovereigns have had a windfall from US inflation. And these are those countries that have issued the largest amount of dollar denominated long term fixed rate liabilities.

As the figure shows the US is obviously the largest issuer of dollar debt because it adds to treasuries its own money base. We estimate that the unexpected US inflation shock has reported a gain of 2 trillion dollars to the US government. The governments of other dollarized economies such as Lebanon, Panama, Bahrain, or Venezuela are also big winners. In all governments other than the US government have enjoyed a windfall of around 100 billion dollars.

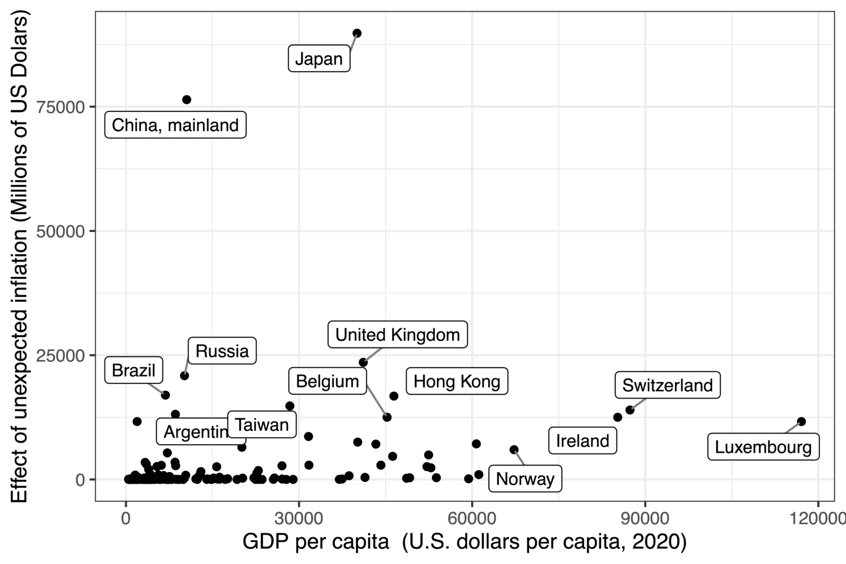

Now, of course, the above reports the gains from the dilution of liabilities to sovereigns. But many countries (and here we are referring to all residents and not just the government) also have large holdings of US dollar denominated long term fixed rates. Those countries suffer a reduction in the real earning power of their assets due to US inflation. In fact, we show that a quarter of the 2 trillion gained by the US is paid abroad, mostly by China and Japan as shown in my last graph.

All in all, this means that the current upsurge in inflation has a larger redistributive effect than in the past, a feature that adds a new dimension to the current inflation drama.

We may then conclude that inflation has come back in its former self. But we were less prepared for it. In this sense the current outlook is somewhat different.